Roy Cook, editor

This special time of the year, Winter Solstice, is the designated time for storytelling. While many are comfortable around the wood fire and sleepy eyes close into the memories of times past.

Long ago, when the world was new, there were seven boys who used to spend all their time down by the townhouse playing the gatayû'stï game, rolling a stone wheel along the ground and sliding a curved stick after it to strike it. Their mothers scolded, but it did no good, so one day they collected some gatayû'stï stones and boiled them in the pot with the corn for dinner. When the boys came home hungry their mothers dipped out the stones and said, "Since you like the gatayû'stï better than the cornfield, take the stones now for your dinner."

The boys were very angry, and went down to the townhouse, saying, "As our mothers treat us this way, let us go where we shall never trouble them anymore." They began a dance--some say it was the Feather dance-and went round and round the townhouse, praying to the spirits to help them. At last their mothers were afraid something was wrong and went out to look for them. They saw the boys still dancing around the townhouse, and as they watched they noticed that their feet were off the earth and that with every round they raised higher and higher in the air. They ran to get their children, but it was too late, for then, were already above the roof of the townhouse--all but one, whose mother managed to pull him down with the gatayû'stï pole, but he struck the ground with such force that he sank into it and the earth closed over him.

The other six circled higher and higher until they went up to the sky, where we see them now as the Pleiades, which the Cherokee still call Ani'tsutsä (The Boys). The people grieved long after them, but the mother whose boy had gone into the ground came every morning and every evening to cry over the spot until the earth was damp with her tears. At last a little green shoot sprouted up and grew day by day until it became the tall tree that we call now the pine, and the pine is of the same nature as the stars and holds in itself the same bright light.

Often times there are amazing accounts of events many thousands of miles and languages apart from familiar stories: A long time ago several young men made up their minds to find the place where the Sun lives and see what the Sun is like. They got ready their bows and arrows, their parched corn and extra moccasins, and started out toward the east. At first they met tribes they knew, then they came to tribes they had only heard about, and at last to others of which they had never heard.

Next: There was a tribe of root eaters and another of acorn eaters, with great piles of acorn shells near their houses. In one tribe they found a sick man dying, and were told it was the custom there when a man died to bury his wife in the same grave with him. They waited until he was dead; when they saw his friends lower the body into a great pit, so deep and dark that from the top they could not see the bottom. Then a rope was tied around the woman's body, together with a bundle of pine knots, a lighted pine knot was put into her hand, and she was lowered into the pit to die there in the darkness after the last pine knot was burned.

The young men traveled on until they came at last to the sunrise place where the sky reaches down to the ground. They found that the sky was an arch or vault of solid rock hung above the earth and was always swinging up and down, so that when it went up there was an open place like a door between the sky and ground, and when it swung back the door was shut. The Sun came out of this door from the east and climbed along on the inside of the arch. It had a human figure, but was too bright for them to see clearly and too hot to come very near. They waited until the Sun had come out and then tried to get through while the door was still open, but just as the first one was in the doorway the rock came down and crushed him. The other six were afraid to try it, and as they were now at the end of the world they turned around and started back again, but they had traveled so far that they were old men when they reached home.

A

Cherokee lady, who also experienced amazing accounts of events in our

recent history of the last century, came to a special point in her long

life. In 2004, when she was 96 years old, Mary Golda Ross asked her niece

to make her something very special: the first traditional Cherokee dress

that Ross, the great-great-granddaughter of renowned Chief John Ross,

would ever own.

A

Cherokee lady, who also experienced amazing accounts of events in our

recent history of the last century, came to a special point in her long

life. In 2004, when she was 96 years old, Mary Golda Ross asked her niece

to make her something very special: the first traditional Cherokee dress

that Ross, the great-great-granddaughter of renowned Chief John Ross,

would ever own.

Because Ross, after a lifetime of high-flying achievement as one of the nation’s most prominent women scientists of the space age, wanted to wear her ancestral dress to the 2004 opening of the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of the American Indian.

In the past 12 months, the museum has received a bequest of more than $400,000 from Mary G. Ross, who died in April 2008, only three months shy of her 100th birthday

“She was a strong-willed, independent woman who was ahead of her time,” said her Oneida friend Norbert Hill, recent past chairman of the National Museum of the American Indian’s Board of Trustees, “and a proud woman who never forgot where she was from.”

Mary G. Ross—whose Cherokee lineage includes leaders and teachers and who herself now figures in that lineage as the Cherokee rocket scientist—spent her century of life looking mostly into the future.

Born

in 1908 on her parents’ allotment in the foothills of the Ozarks,

she was one year younger than the state of Oklahoma. It had been 70 years

since her ancestor led his people over the Trail of Tears. She excelled

in math, and her first career was as a young high school math and science

teacher. By 1937, Ross remembered asking herself, “Are you going

to go out and see anything of the world, or are you going to stay in Northern

Oklahoma?”

Born

in 1908 on her parents’ allotment in the foothills of the Ozarks,

she was one year younger than the state of Oklahoma. It had been 70 years

since her ancestor led his people over the Trail of Tears. She excelled

in math, and her first career was as a young high school math and science

teacher. By 1937, Ross remembered asking herself, “Are you going

to go out and see anything of the world, or are you going to stay in Northern

Oklahoma?”

She went to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and, at age 29 in 1937 and later went to Santa Fe, N.M., as the girls’ adviser at a new school for American Indian artists. In the summers Ross pursued a master’s degree in mathematics at the University of Northern Colorado. While there, she took every astronomy class the school had, and read every book about the stars. The clear night sky in Colorado fascinated her.

She was hired by the Lockheed Corporation as a mathematician in 1942 and worked on improving the aero elasticity of the P-38 Lightning fighter plane—the first to go more than 400 mph.

By 1948, Ross was on the ground floor of what would become the space race. In 1952 Lockheed asked her to be one of 40 engineers in what became known as the Lockheed Skunk Works, a super-secret think tank led by legendary aeronautics engineer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. It was the start of Lockheed Missiles & Space Co., a major consultant to NASA based in Sunnyvale, Calif.

Ross was 45, the only woman and the only Native American. Most of the theories and papers that emerged from that Lockheed group, including those by Ross, are still classified.

Around the time of the Soviet Union’s 1957 launch of Sputnik, Ross moved into the public eye. In 1958 she appeared on the television show “What’s My Line?” It took contestants many guesses before they realized that the smiling woman in a V-necked, sleeveless black dress in fact, as the caption read, “Designs Rocket Missiles and Satellites (Lockheed Aircraft).”

One San Francisco-area newspaper article from 1961 called Ross “possibly the most influential Indian maid since Pocahontas,” and noted that she was “making her mark in outer space.” She told the interviewer, “I think of myself as applying mathematics in a fascinating field.”

Another article from the time noted that Ross, who had yet to see a rocket blast off, believed that women would make “wonderful astronauts.” But she said, “I’d rather stay down here and analyze the data.”

Ross retired from Lockheed at age 65 in 1973, and turned her attention to the next generation of Native Americans and women in engineering.

“To function efficiently, you need math,” she said later in life. “The world is so technical, if you plan to work in it, a math background will let you go farther and faster.”

One

of the few regrets she ever mentioned was that she had spent so much of

her life apart from Indian people.

One

of the few regrets she ever mentioned was that she had spent so much of

her life apart from Indian people.

At 96, Ross was looking ahead again—to the long-anticipated Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. In the opening procession, she stepped out of her electric wheelchair on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and walked for half a block.

“She felt she was a part of history being made, again,” said friend Norbert Hill.

Mary

Ross too was a star in the vast milky way of the sky.

Mary

Ross too was a star in the vast milky way of the sky.

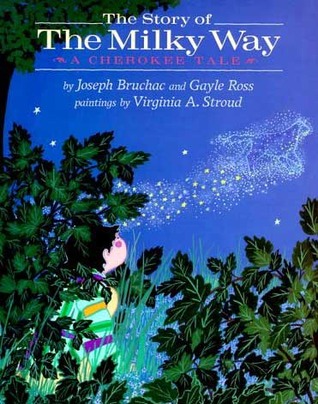

Some people in the south had a corn mill, in which they pounded the corn into meal, and several mornings when they came to fill it they noticed that some of the meal had been stolen during the night. They examined the ground and found the tracks of a dog, so the next night they watched, and when the dog came from the north and began to eat the meal out of the bowl they sprang out and whipped him. He ran off howling to his home in the north, with the meal dropping from his mouth as he ran, and leaving behind a white trail where now we see the Milky Way, which the Cherokee call to this day Gi`lï'-utsûñ'stänûñ'yï, "Where the dog ran."