By Roy Cook

A country with no regard for its past, will do little worth remembering in the future. ---Abraham Lincoln

Some

USA groups are planning a celebration of the 200th anniversary of President

Abraham Lincoln’s birth on Febuary12, 2009. There are some bitter

views as to his legacy with the First Americans. Also it is a tragic irony

that his personage is on display on the Black Hills of the Dakota. Examine

the political and legal issues of this tragic Minnesota affair under his

watch. It is the largest mass execution of American people in the history

of the United States.

Some

USA groups are planning a celebration of the 200th anniversary of President

Abraham Lincoln’s birth on Febuary12, 2009. There are some bitter

views as to his legacy with the First Americans. Also it is a tragic irony

that his personage is on display on the Black Hills of the Dakota. Examine

the political and legal issues of this tragic Minnesota affair under his

watch. It is the largest mass execution of American people in the history

of the United States.

In peace and friendship the Dakota ceded 21 million acres, over half the territory of Minnesota, many waters in Dakota language; in the 1851 Traverse des Sioux Treaty of Peace and Friendship. Despite federal promises of protection and assistance, at the Minnesota River reservations, the Dakota Santee were badly mistreated by corrupt federal Indian agents and contractors. This non-fulfillment of treaty promises issue resulted in the Dakota Santee Sioux being found guilty by military court of joining in the so-called "Minnesota Uprising." This avoidable tragedy was actually part of the wider Indian conflicts that plagued the West during the second half of the nineteenth century. For nearly half a century, the US govt. had been selling land in the west to pay for past and current wars domestic and abroad. Anglo and German settlers invaded the Dakota Santee Sioux territory in the beautiful Minnesota Valley, and government pressure gradually forced the Dakota Indians to relocate to smaller reservations along the Minnesota River.

Abuses

continued at the Minnesota River reservations during July 1862 with the

agents pushing the Dakota Indians to the brink of starvation by refusing

to distribute stores of food because they had not yet received their customary

kickback payments. The contractor Andrew Myrick callously ignored the

Santee's pleas for help. He said, “Let them eat grass.”

Abuses

continued at the Minnesota River reservations during July 1862 with the

agents pushing the Dakota Indians to the brink of starvation by refusing

to distribute stores of food because they had not yet received their customary

kickback payments. The contractor Andrew Myrick callously ignored the

Santee's pleas for help. He said, “Let them eat grass.”

Outraged and at the limits of their endurance, the Dakota Santee finally struck back, killing Anglo settlers and taking women as hostages. The initial efforts of the U.S. Army to stop the Santee warriors failed, and in a battle at Birch Coulee, Dakota Santee Sioux killed 13 American soldiers and wounded another 47 soldiers. However, on September 23, a force under the leadership of General Henry H. Sibley finally defeated the main body of Dakota Santee warriors at Wood Lake, recovering many of the hostages and forcing most of the Indians to surrender. The subsequent five-minute trials of the prisoners gave little attention to the injustices the Indians had suffered on the reservations and largely catered to the popular desire for revenge. Injustice moved very rapidly through the trials of the accused. Here, in its entirety, is Case # 241: Pay-pay-sin

Prisoner states, “I was at Fort Ridgley and stood near the stable. I fired three shots.”

The Military Tribunal found him guilty and ordered he be hanged.

The revered Anglo- Saxon principle of law that a person is considered innocent until proven guilty was reversed in the case of the Indians. Authorities in Minnesota asked President Lincoln to order the immediate execution of all 303 Indian males found guilty. President Lincoln was under heavy political pressure to acknowledge states rights but he objected to what he viewed as wholesale slaughter. Lincoln was concerned with how this would play with the Europeans, whom he was afraid were about to enter the war on the side of the South. He wired the commanding officer to stay the executions and forward the "full and complete record of each conviction." He also ordered that any material that would discriminate the guilty from the questionable be included with the trial transcripts. Lincoln and Justice Department officials reviewed every case. Episcopalian Bishop Whipple pleaded for clemency but Military leaders and the Minnesota state politicians warned Lincoln that anything less than large-scale hangings would result in widespread white outrage and more violence against the Indians. After review, the president pardoned 265 of the 303 condemned Indians, approving a total of 38 executions. He offered the following compromise to the politicians of Minnesota: If they would pare the list of those to be hung down to 39. In return, Lincoln promised to kill or remove every Indian from the state and provide Minnesota with 2 million dollars in federal funds. This eagerness to buy cooperation from the state in spite of the fact that the Federal government still owed the Sioux 1.4 million for the land is both tragic and ironic.

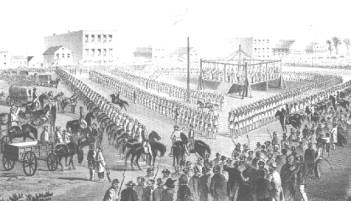

So,

on December 26, 1862, the Great Emancipator ordered the largest mass execution

in American History, where the guilt of those to be executed was entirely

in doubt. After 38 of the condemned men were hanged on the 26 of December,

the day after Christmas, in 1862 in what remains the largest mass hanging

in United States history, the other prisoners continued to suffer in the

concentration camps through the winter of 1862-63.

So,

on December 26, 1862, the Great Emancipator ordered the largest mass execution

in American History, where the guilt of those to be executed was entirely

in doubt. After 38 of the condemned men were hanged on the 26 of December,

the day after Christmas, in 1862 in what remains the largest mass hanging

in United States history, the other prisoners continued to suffer in the

concentration camps through the winter of 1862-63.

In late April of 1863 the remaining condemned men, along with the survivors of the Fort Snelling concentration camp, were forcibly removed from their beloved homeland in May of 1863. They were placed on boats, which transported the men from Mankato to Davenport, Iowa where they were imprisoned for an additional three years. Those from Fort Snelling were shipped down the Mississippi River to St. Louis and then up the Missouri River to the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota.

Happy birthday but shame on you, Mr. Lincoln, not all Americans, especially the First Americans, sees you as the ’great emancipator.’

What do Sioux Indians think of this issue today?

A solemn ride to realize a dream

A group of American Indians is taking part in a 2005 weekend horseback ride to honor the memory of 38 Indians hanged in Mankato in 1862. The horseback trek came to one of the riders, Jim Miller of South Dakota, in a dream.

They rode east along the highway into the December morning sun Friday, 11 American Indians on horseback, each carrying an eagle feather, led by a man from Porcupine, S.D., who had dreamt last March that this day would come.

They rode to remember their ancestors. Thirty-eight of them were hanged in Mankato on Dec. 26, 1862, in what has been called the largest mass execution in American history.

More Indians on horseback are expected to join the procession during the weekend ride. It will end Monday, when they will enter Mankato near the site where gallows once stood and conduct a final ceremony.

"I'm a little anxious," said Jim Miller, 57, holding a sacred staff covered with buffalo fur. He was sitting atop the lead horse, which was pawing the snow-covered ground outside the community center on the Lower Sioux Indian Community in Morton. "I'm happy -- I'm fulfilling my dream," he added.

Miller, an Oglala Sioux on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, said he had had a dream where Indian horse riders descended on Mankato; he told Alex White Plume, vice chairman and acting president of the tribe, about it. White Plume told Weldon Wolfchild, chair of the Lower Sioux Community, and they agreed to organize the ride.

On Thursday night, about 150 Indians gathered at the community center to share a meal and hold a ceremony to send off the riders. Sitting in the crowd, 73-year-old Roland Columbus talked about the song his grandfather, Moses Hisday, wrote, memorializing the 38 executed Indians who were hanged after they rose up in a confrontation with white settlers.

Hisday taught Columbus the song, written in the Sioux language, in the late 1930s and told him to sing it wherever he could, to remind people what happened.

"From the clouds on high, they're looking down," the song begins. "The Indians that you hung are looking down. All of those that have gone before, they are looking down." When they arrive in heaven, the song concludes, Indians will be standing in the front ranks.

Columbus' great-great grandfather was Little Crow, the Sioux leader killed by settlers in 1863.

Wolfchild, 59, said that the riders planned to camp out each night before riding to the hanging site Monday. According to Indian accounts, some Indians seized after the revolt was suppressed were taken on oxcarts, bound hand and foot, from Morton to Mankato in 1862.

Along the way, angry settlers assaulted them, and some, says Wolfchild, were killed. This weekend's horse ride retraces the trip, though the exact route is unknown, he said.

Wolfchild says that his great-great-grandfather, Chief Medicine Bottle, was one of two Indians hanged at Fort Snelling rather than in Mankato. Kenneth Carley, who wrote the book, "The Sioux Uprising of 1862," said Medicine Bottle was "sentenced to death on rather flimsy evidence."

Some accounts blame the revolt on the Indians who killed women and children.

But Wolfchild, a Vietnam War veteran, says he understands the chaos of war. He blames the revolt on failed crops for two consecutive years and the failure of the U.S. government to ship gold to the Indians, who had been promised it in return for land they ceded after an 1851 treaty. There was no money to buy food, the Indians were starving, and some of the younger Indians began the war, Wolfchild said.

Steve Crooks, 62, took from an envelope the manuscript of a 1937 interview with his grandfather, George Crooks, who was 7 in 1862.

"When the subject of the 1862 massacre comes up, why not take time to think and consider both sides of the story before you condemn the Indians for trying to protect their own," George Crooks said. "Try to remember that the white people took everything the Indian had to live for away from him."