WA

AMAAY KWAKAS.

WA

AMAAY KWAKAS.

Yellow Sky

was acknowledged during a recent Wildcat song practice session and according

to Jon Mesa Cuero, “This song was composed in 1848 or 1849. It presents

the impressions of the composer starting a jouney North from Tecate in

the Sun wise circle of the Tipai villages. Yellow Sky was a man who was

very slender and tall.” (One of the physical characteristics of the

River people, especially the Quechan, is their height. Many well over

six and a half feet.) Thus, according to Jon, “This man was so tall

he could have painted the sky. This is why he was called "pinta el

cielo amarillo" in Tipai, Mai Ta Quas, Paints the Sky Yellow.”

Yellow Sky's father was Kwaaymii and his mother was Quechan (Yuma). Yellow

Sky traveled back and forth to the Colorado River area every spring. He

returned to stay on the Laguna Reservation in 1888. He had a small dwelling

just north of the still existing Tom Lucas' cabin on the main Kwaaymii

village. In his later years SuSaana Klietch, Tom's grandmother, would

often take care of him. He would still access the traditional trails to

the Ipai and Tipai communities that are along and around the Cuyamaca

mountain region. He was frequently recalled as one of the last true traditional

living individuals wearing only basic regalia.

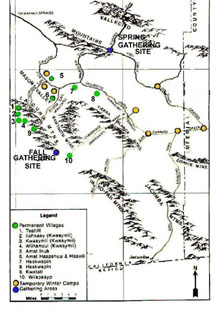

A further

association with the Kwaimii is the Nymii Wilcat song the makes direct

reference to the southern village site Ewiiaapaay or Cuyapaipe. Refer

to village map for song clip and location. (Click map to enlarge and hear

clip.)

Jon is a native speaker of Tipai and is knowledgably of the distinctions

between the different dialects of the Tipai language. In fact there are

many subtleties beyond the variations between Ipai and Tipai. It is not

unusual to find a variation in spelling or grammar that the particular

Band is very comfortable with but may give headaches to linguists. See

the Nymii,

Wildcat page for more on this song style.

The

timeless quality of the songs and stories carry the Tribal culture from

the timeless past into the yet unknown future. As such the chronological

dates in many of the traditional Native American stories are fluid. This

brings to mind another insight into the oral tradition and the richness

of Native American literature. Jon once told us that his father taught

him this same song about Ewiiaapaay over fifty years ago when he was a

child. As the years went by and he became an adult and caught up in the

day-to-day efforts to provide for a family he had less of a grasp of those

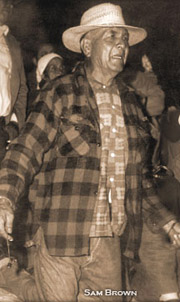

songs he had been taught as a boy. ‘Old’ Sam Brown from Viejas/Los

Conejos reminded him about the Ewiiaapaay story. As he was repeating the

words the tune to the song emerged and he was able to place this Ewiiaapaay

song in a sequence of village/Band geography. Recall and talent are major

influences on each storyteller’s ability to bring the event to life.

Fluidity, almost as much, is the inspiration that sparks the humanity

and glow in our heart to share: thoughts, emotion, joy, sadness and historical

events.

The

timeless quality of the songs and stories carry the Tribal culture from

the timeless past into the yet unknown future. As such the chronological

dates in many of the traditional Native American stories are fluid. This

brings to mind another insight into the oral tradition and the richness

of Native American literature. Jon once told us that his father taught

him this same song about Ewiiaapaay over fifty years ago when he was a

child. As the years went by and he became an adult and caught up in the

day-to-day efforts to provide for a family he had less of a grasp of those

songs he had been taught as a boy. ‘Old’ Sam Brown from Viejas/Los

Conejos reminded him about the Ewiiaapaay story. As he was repeating the

words the tune to the song emerged and he was able to place this Ewiiaapaay

song in a sequence of village/Band geography. Recall and talent are major

influences on each storyteller’s ability to bring the event to life.

Fluidity, almost as much, is the inspiration that sparks the humanity

and glow in our heart to share: thoughts, emotion, joy, sadness and historical

events.

WA

AMAAY KWAKAS (Yellow sky) is a historical Native American from the

turn of the 20th century. He was documented and photographed by the Mesa

Grade resident and prominent ethnographer Edward H. Davis.

In 1915, 28 years after Davis settled in Mesa Grande, a representative

of the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, made his way up

the mountain to inspect the collection. After negotiations, he purchased

almost the entire collection for the museum. That same year, perhaps with

the funds from the sale of his collection, Davis built Powam Lodge, a

resort hotel with an all-Indian motif. The lodge soon became popular,

attracting visitors to the clear air of the mesa and the opportunity to

hear its proprietor, a talented storyteller, regale the guests with accounts

of his experiences among the Indian people of the Southwest. Davis encouraged

local Kumeyaay artisans to make traditional items of quality to sell at

Powam Lodge, and often hired Indian performers.

A 1916 meeting in San Diego with George G. Heye, the founder and director of the Museum of the American Indian, resulted in Davis accepting an offer to be a field collector of ethnological specimens for the museum. He was delighted. In a 1931 article he wrote for Touring Topics, Davis recalled, “This gave me the very job I had long hoped to create for myself”. It began a relationship with George Heye and his museum that lasted, intermittently, for seventeen years. Historical aside: The New York Heye Collection was a large core collection for the most recent National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C.