|

For 10 millennia

before the Spanish and other European settlers arrived in California,

the Kumeyaay Indian Nation lived in the area now divided into San Diego

and Imperial Counties and Baja Norte. Although this nation of original

inhabitants has been called Southern Diegueño, Diegueño-Kamia,

Ipai-Tipai and Mission Indians, the people prefer to be known as Kumeyaay.

Yuman-speaking people of Hokan stock, Kumeyaay

territory extended from the Pacific Ocean east to the Colorado River,

north to Warner Springs Valley and south to Ensenada. Neighboring nations

to the northeast and east were the San Lusieño, Cupeño

and Cahuilla. While southern California Indian nations shared many characteristics,

there was little uniformity in language, customs, political and social

organization or economic resources.

Indian nations throughout California, and North

and South America were comparable to the multiple cultures, governments,

religions, economic resources and languages of independent nations that

abounded on the European, African and Asian continents in the year 1000

AD.

The Kumeyaay planted trees and fields of grain;

grew squash, beans and corn; gathered and grew medicinal herbs and plants,

and dined on fresh fruits, berries, pine nuts and acorns. Kumeyaay fished,

hunted deer and other animals, and were known for basket weaving and

pottery. The people had sophisticated practices of agriculture, plant

and animal husbandry; maintained wild animal stocks; controlled erosion

and overgrowth; built dams; created watersheds and stored groundwater.

A federation

of autono-mous, self-governing bands, or clans, the Kumeyaay had clearly

defined territories that included individual and collectively owned

properties. The Kumeyaay united in defense of their territory and communicated

by foot couriers. Throughout this vast area trails were forged by the

Kumeyaay through the mountains, deserts and river valleys for trading,

gathering for funerals, marriages and competitive games with each other

and neighboring nations. A federation

of autono-mous, self-governing bands, or clans, the Kumeyaay had clearly

defined territories that included individual and collectively owned

properties. The Kumeyaay united in defense of their territory and communicated

by foot couriers. Throughout this vast area trails were forged by the

Kumeyaay through the mountains, deserts and river valleys for trading,

gathering for funerals, marriages and competitive games with each other

and neighboring nations.

A band's territory extended anywhere from 10

to 30 miles, along a stream and tributaries. It included trails, shared

hunting, religious, ceremonial and common gathering areas. However,

specific land tenured by families and individuals provided the economic

foundation of the Kumeyaay existence. Property was generally passed

from father to son.

Each family independently planted and maintained

fields of grain, grass and other annuals, shrubs, tree groves, cornfields,

quarries and hot and cold springs, clay beds and basket grass clumps.

However, sharing the produce for the band's benefit was assumed. Territory

belonging to a band often included adjacent holdings stretching from

the mountains and river plains, to the coast.

The Kumeyaay took advantage of the different

climatic zones in the region, surviving fluctuations in the climate

by rotating domestic crops and living off varieties of food sources

in the different ecological systems.

Sacred lands were shared. Creation stories and

religious rituals were tied to specific locations, or holy lands, just

as with the Hebrews, Christians and Muslims. One such place is Kuuchamaa,

or Tecate Peak. Another is Wee-ishpa, or Signal Mountain. Burial grounds

were sacred, and still are to this day. Each band had worship areas

restricted to religious and tribal leaders.

Generally peaceful by nature, the Kumeyaay social

and governmental customs of tolerance and individual freedom spawned

independent people.

The social structure of the bands included the

shiimull, or ancestral descent group, governed by a hierarchy of kwaaypaays.

The shiimull often had family loyalties and relatives that extended

beyond the band through marriage. In 1769, when the Spanish arrived,

between 50 and 75 shiimull, or bands existed. Each included 5 to 15

family groups.

The kwaaypaay was usually the male head of a

shiimull. He inherited the position from his father, but was not necessarily

from the band he led. The kwaaypaays were raised to become leaders.

A common practice was for the kwaaypaay of one band to be selected from

another band, thus ensuring unity among the clans. Also, since the primary

duty was to maintain harmony and arbitrate disputes, a kwaaypaay without

relatives in the band to prejudice decisions was more impartial and

fair. Even though the leadership was drawn from among the sons of all

kwaaypaays, the final choice, and approval of their leader, belonged

to the band.

Each kwaaypaay, or captain or chief, as they

came to be called, had an assistant called the speaker, and a council

of kuseyaay. Composed of male and female priests, scientists, doctors

and other specialists, kuseyaays served as advisers in ecology, resource

management, healing, and the spiritual and religious practices of the

tribe.

The kwaaypaay called upon these counselors to

assist in providing information and making decisions for the tribe's

welfare. Once a decision was made, it had the force of law.

However, each family was free to follow and

participate in the decision, or break off from the band; leave the band's

territory and pursue its own course of action without punishment or

retribution.

The Kumeyaay lived life through songs. They

danced and sang to celebrate, mourn and teach. Culture, traditions,

history and social values were transmitted through songs. Songs taught

everything the people needed to know to survive. There were songs about

the environment such as salt, wildcats and plants. There was no written

language. Songs contained the collective wisdom and memories of the

Kumeyaay people.

Individuals and clans had songs. Spiritual and

creation songs and dances, such as the Bird Song and Eagle Dance, taught

moral lessons and connected people with the ancestors and the meaning

of life and death.

In 1542, life began to change for the Kumeyaay.

No longer a story of a culture and people evolving, living, dying, shaping

and being shaped by the environment, it was a time of death caused by

hunger and disease, occupation, slavery, rape and genocide.

The last 500 years of the millennium for the

Kumeyaay was a time of survival and conquest. The shared history became

a story of clashing cultures and the struggle of the Kumeyaay to adapt,

yet maintain their cultural identity in a changed world.

First came the Spanish, followed by the Mexican

government and the United States. Each believed the land and people

who had lived here for millennia existed for their use and abuse.

Unable to provide protection from the influx

and military might of the newcomers, removed from food sources and land,

unable to speak the language or understand the customs of the immigrants,

and without legal protection of civil rights, the Kumeyaay became totally

dependent upon a hostile populace, strangers in their own land. Denied

customs, culture, social and political traditions, the Kumeyaay became

strangers to themselves.

Despite common beliefs that Californian Indians,

beleaguered of soul and body, crept away to die, these ancestors survived.

Their story of sacrifice and courage and belief that the Kumeyaay would

reclaim a place in this land is as positive and encouraging as their

suffering was devastating.

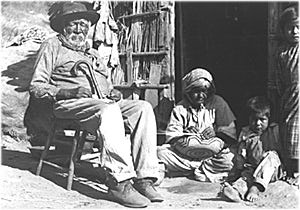

Generally peaceful by nature, a Kumeyaay band would include

as many as 15 family groups.

|

1769-1822 The Mission Period

In September 1542, the coastal Kumeyaay encountered

the first European, Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo, when his ship sailed into

San Diego Bay.

Then, in 1769, the Spanish sent a colonizing

force into upper California.

Spanish army units founded a presidio (army

post) in San Diego Bay and Franciscan Juan Crespi arrived with the first

overland group of Spanish missionaries and soldiers. He was followed

in July by Father Junipero Serra, with a group led by Gaspar de Portola.

Father Serra, founder of the Mission San Diego, and others like him

were charged with bringing the natives to Catholic Christianity. Thus

began the mission years for the Kumeyaay.

The directive of the priests was to educate

the natives in "civilized pursuits and to make them working class citizens

of the Spanish Empire." Once converted and properly indoctrinated in

the customs of the church and the realm, these baptized Indians would

be granted a piece of land. The local missions also were expected to

supply the army with food, livestock and laborers for mission pueblos

and private ranch holdings granted by the Spanish government.

Kumeyaay coastal land was confiscated and the

people captured and forced to work for the Spanish. Soldiers scoured

the countryside for Indians to be rounded up for conversion and indentured

slave labor. After a period of indoctrination and servitude, some were

released to return to their homes. The women were often raped and used

as property of the militia. Unmarried Indian girls, the sick, some elderly

and men trained as specialists in leather and woodworking, carpenters,

farmers and blacksmiths were permanently kept at the mission, often

against their will.

To avoid capture the Kumeyaay fled east to the

mountains to make new homes. Kumeyaay ritual and spiritual practices

were outlawed. The Kumeyaay revolted against forced servitude and abduction.

In 1776, there were a number of uprisings and skirmishes, one destroying

the San Diego Mission, which was rebuilt on another location. The Spanish

forces moved inland, taking Kumeyaay lands in Santee, El Cajon, Jamacha

and Jamul to gain control of better water resources.

Death stalked the Kumeyaay in many ways. Without

natural immunities the Kumeyaay, exposed to European diseases, died

by the thousands as smallpox and measles spread through the villages.

1822-1848 Mexican Period

Following the Mexican Revolution and founding

of the Republic of Mexico in 1822, the Spanish holdings were secularized.

During the Mexican period, the missions became parish churches and mission

lands, rancheros. Prior commitments made to Hispanicized Kumeyaay for

small plots of land by the Spanish were dismissed. Mexican governors

gave the best mission lands to Mexican nationals, and conceded large

land grants, absorbing farms of Hispaniized Indians granted by the Spanish,

as well as Kumeyaay villages within their boundaries.

Kumeyaay living on former mission properties

were turned over to Mexican nationals to serve as peon labor. Missions

were placed under majordomos, who used the Indians as servants for their

large families. Majordomos allocated passes to the Kumeyaay laborers

to leave the rancheros to visit their families, and sent patrols to

recapture those who did not return. The Kumeyaay became prisoners on

their own land, trading one form of enslavement for another.

When repeated requests to the Mexican government

by the Kumeyaay about abuses of their land and water rights were ignored,

inland bands led numerous uprisings and revolts. In San Diego, Mexicans

seldom left the presidio or pueblos without military guard.

Eventually, the United States moved to acquire

the California territories. In December 1846, the U.S. Army led by Gen.

Stephen Watts Kearny passed through Yuma, San Felipe, Warners Valley,

Santa Ysabel and San Pasqual, destroying Kumeyaay homes for firewood.

The Kumeyaay and other Indians were friendly

toward the Americans, hopeful that this new government would keep promises

to settle the land disputes and treat the Indians fairly. During the

battle of San Pasqual between the Mexicans and U.S. Army, the Kumeyaay

aided General Kearny. After the battle, they guided him to San Diego.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transferred

California to the United States and guaranteed existing land titles,

all rights and immunities, and religious freedom to Mexican citizens.

All these rights also were to be applied to baptized Indians who became

Mexican citizens; however they were rarely enforced for the Christian

Kumeyaays, and never for the traditional Kumeyaays.

Anthony R. Pico is tribal chairman of the Viejas Bank

of Kumeyaay Indians.

Click here for Part

2

|

A federation

of autono-mous, self-governing bands, or clans, the Kumeyaay had clearly

defined territories that included individual and collectively owned

properties. The Kumeyaay united in defense of their territory and communicated

by foot couriers. Throughout this vast area trails were forged by the

Kumeyaay through the mountains, deserts and river valleys for trading,

gathering for funerals, marriages and competitive games with each other

and neighboring nations.

A federation

of autono-mous, self-governing bands, or clans, the Kumeyaay had clearly

defined territories that included individual and collectively owned

properties. The Kumeyaay united in defense of their territory and communicated

by foot couriers. Throughout this vast area trails were forged by the

Kumeyaay through the mountains, deserts and river valleys for trading,

gathering for funerals, marriages and competitive games with each other

and neighboring nations.