|

Antonio

Garra: Tarnished California Gold

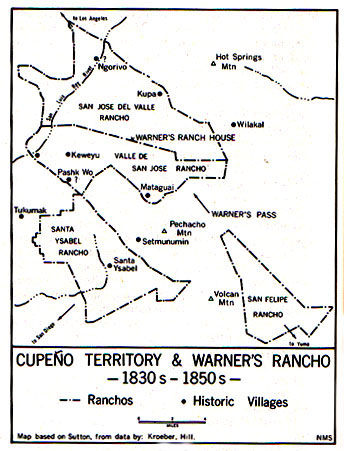

Yesterday,

living at Wilakal was Antonio Garra and his son, who went under the

same name. The elder Garra had been educated at San Luis Rey Mission

and was a willing listener to the whispered suggestions of Bill Marshall,

Anglo ex-sailor who had encouraged the Pauma Valley Indians in the murder

of the eleven Californios. Marshall assured Garra that the Californios

and Mexicans, once a revolt had begun, would come to their assistance

against the Americans. Garra dispatched runners to all of the Indian

tribes between the coast and the Colorado River, and from the San Joaquin

Valley south into the upper country of Baja California. One message

went to Juan Antonio, a leader of the Mountain Cahuilla, one of three

branches of the Cahuilla Indians who roamed the eastern mountain and

desert area of Southern California and who never came under the direct

influence of the missions. Juan Antonio, it will be remembered, had

helped the Californios in the capture of the Indians who had

participated in the Pauma massacre and, on his own initiative, had slaughtered

the captives, men, women and children. In his letter to Juan Antonio,

Garra wrote: This is

an explanation you already know who we are going to do, secure each

point of rancherias since this thing is not with their capitanes.

My will is for all, Indians and Anglos, since by the wrongs and damages

they have done, it is better to end us at once. Now those of Lower California

and of the River are invited; but those of the River will not come soon.

They move slow. If we lose this war, all will be lost -- the world if

we gain this war; then it is forever; never will it stop; this war is

for a whole life. Then so advise the Anglo people, that they may take

care. Wild reports raced through

the hills. It was believed that the Cahuillas were to descend on Los

Angeles, and the Yuma and other Colorado River Indians were to cross

the mountains and join the Diegueños and Luiseños in driving out the

Americans. Gen. Bean, who had urged

the Indians not to pay taxes, (Take special note of this initial legal

counsel!) now was faced with a major Indian war. As they had done many

times in the past, the Dons fled their ranchos for the safety of San

Diego. Friendly Indians left their valley and mountain homes and sought

the protection of the Anglos. Juan Bandini came up from Lower California

and reported the Indians far down the peninsula were in a state of rebellion.

Because of the shortage of guns and ammunition, all blacksmiths were

put to work making lances, as had been done before the Battle of San

Pasqual.

Warner's ranch was attacked

on the night of November 21, 1851. Juan (John) Warner had sent his family

away, and he had remained behind with a hired man and an Indian boy

who had been placed with him in exchange for a bushel of corn. One hundred

Indians surrounded the trading post, and Warner and his hired man held

them off until their ammunition ran out. They then fled from the ranch

house toward horses that had been kept saddled for just such an emergency.

Warner and the Indian boy escaped but the hired man was killed. The

Indians burned the house, drove off the stock, and then proceeded to

the Hot Springs three miles away where they murdered four Americans

who had gone there from San Diego to rest. One of them was Levi Slack,

merchant partner of E. W. Morse. Four American sheepherders were killed

near the Colorado River crossing. San Diegans prepared to defend

the town and a volunteer company was organized under Maj. E. F. Fitzgerald,

of the U.S. Army, as commander. Cave J. Couts was named captain and

Sheriff Haraszthy, first lieutenant. In a letter to his mother and sister,

dated December 2, 1851, Thomas Whaley wrote: . . . The first attack the

Indians made was upon the rancho of J. J. Warner, member of our State

Legislature, burning his house, Stealing everything belonging to him

and murdering a man in his employ. Four men have been murdered upon

the Gila and four more Americans from this place at the Springs of the

Agua Caliente who had gone there for their health . . . the rancheros

are sending their families to town for better protection . . . I am

well armed with a brace of Six Shooters and have a horse ready to Saddle

at any moment. Lt. Sweeny, who had been

left with a small body of soldiers at Fort Yuma, was joined by Capt.

John W. Davidson and sixteen additional men who had been sent from San

Diego as a relief party, and by the parties of Maj. Henry L. Kendrick

and Capt. L. Sitgreaves, who had been engaged in exploring the Colorado

River. Though they now had thirty men it was decided to abandon the

fort on December 6 because of a lack of supplies, and take the road

to San Diego. Cave Couts, in a letter to Abel Stearns, reported that

Kendrick had found the whole desert frontier ablaze. The mountains were

covered with signal fires from Carrizo Creek to Santa Ysabel. An American

by the name of Whitley, living at Cockney Bill's ranch on Volcan Mountain,

told Davidson and Sweeny that Indians had collected from Vallecito,

San Felipe, San Jose and neighboring mountains to attack the military

train but upon seeing the number of soldiers, because of the presence

of Capt. Davidson's men, had given up and now professed only friendship

to the Anglos. At San Pasqual they received

orders to return to Santa Ysabel, where their forces were joined with

those of Majs. Heintzelman and Magruder and about one hundred soldiers

who had been quartered at Mission San Luis Rey. Sweeny and his men were

ordered to protect San Diego, and he took the mountain trail toward

El Cajon and arrived on December 21. The populace, especially the women,

welcomed them with cheers, Sweeny writing that "they looked upon me

as their deliverer from the tender mercies of savages," who, they said,

would have attacked the town if his men had been cut off in the mountains.

This was later confirmed. During the absence of the Army regulars, a

force of recruits had arrived by sea and they also had kept San Diego

in a state of unrest with their drinking and rioting. Their ringleaders

had been placed in irons. Sweeny ordered all 250 recruits to line up

and he reviewed them without a sidearm of any kind. The soldiers were

silent and respectful. A virtual state of mutiny ended. Fitzgerald's Volunteers left

San Diego on December 27 reached Agua Caliente and burned the village

of the Cupeño Indians, and proceeding to the site of Warner's store,

found nothing but ruins and the bodies of two Indians. Haraszthy went

out with a small party and took Marshall and two Indian companions into

custody and delivered them to San Diego for a court martial headed by

himself. The principal evidence against Marshall came from Indians but

it was decided that their testimony could not be accepted before a legal

tribunal. Justice was pre-ordained. Gallows were erected before the

trial began. The court martial made quick

work of Marshall and one of the two Indians captured with him, whose

name has been variously given as Juan Verdugo, or Juan Verde or Gerde.

The San Diego Herald reported on December 18: The trial

of these men was concluded on Friday evening last; on Saturday morning,

it was announced on the Plaza they were to be executed at 2 o'clock

the same day. The Fitzgerald Volunteers were ordered to be on duty at

that time to conduct the prisoners to the scaffold, which had been erected

a short distance out of town, near the Catholic burying grounds. The

graves were dug, and all the preparations made, during the forenoon,

for carrying out the sentence of the court martial. About 2:00 o'clock

the Volunteers were under arms, the people began to gather in considerable

numbers about the Plaza and Court House. A Priest (Fr. Juan Holbein)

was with the prisoners most of the forenoon and accompanied the men

to the gallows, where they received final absolution. They were then

informed that a short time would be allowed them, if they wished to

make any remarks. Marshall was the first to speak . . . He said he was

prepared to die and he hoped that his friends, and the people around

him, would forgive him, that he trusted in God's mercy, and hoped to

be pardoned for his many transgressions. He still insisted that he is

innocent of the crime by which he was about to die . . . Verdugo spoke in Spanish.

He acknowledged his guilt and admitted the justice of the sentence passed

upon him; said he was ready and willing to yield up his life for forfeit

for his crimes and wickedness. The ropes were then adjusted, the priest

approached them for the last time . . . repeated the final prayer, extended

the crucifix, which each kissed several times, when he descended from

the wagon, which immediately moved on, leaving the poor unfortunate

wretches suspended about five feet from the ground. The hanging took place on

December 13, 1851. The site of the executions may have been near the

new Catholic church being erected on a site across the river, and burial

was in an adjoining cemetery. Warner's Indian servant boy was found

guilty of giving false testimony and sentenced to receive twenty-five

lashes. The United States Army forces,

which had established headquarters at Santa Ysabel, divided into

two divisions to take separate routes through the mountains toward the

village of Los Coyotes where the Indians had been holding their councils

of war, and the one under command of Heintzelman was attacked by Indians

led by a chief named Chapuli. The soldiers concentrated their fire on

Chapuli. He was killed, and as the Indians fled up the sides of a mountain,

a second chief was shot dead. The encounter led to the

capture of a number of prisoners in the vicinity of Los Coyotes, among

them a number known to have taken part in the attack on Warner's, and

after a military trial on the spot, four chieftains were condemned to

die, and were executed on Christmas Day while kneeling before their

graves. Some eighty Indians witnessed the executions which took place

at the site of the village near the creek bed. All traces of the village

on the desert route into the mountains first explored by Anza, have

disappeared. At San Diego Fitzgerald's

Volunteers were reinforced by volunteers brought by boat from San Francisco,

who were dubbed "The Hounds," in memory of the hoodlums who had so terrorized

the northern city. Organized as the Rangers, at the call of the governor

to assist if needed at San Diego, they had been ordered disbanded with

news of the success of the military. But they came anyway. They wrought

more harm and misery on San Diego than did the Indians. With no enemy

to fight, they camped in Mission Valley and ranged through Old Town

on drunken sprees and threatened to sack the town. The authorities sent

an appeal to Lt. Sweeny, at the old barracks at La Playa, and he led

a sergeant and eighteen men into Old Town. That same afternoon, Philip

Crosthwaite, a sergeant of Fitzgerald's Volunteers, engaged in a row

with one of the Hounds identified as a Lt. Watkins. Both were wounded

in an exchange of gunfire on the street, and Crosthwaite barely escaped

death, retreating under a heavy fire from other members of the Hounds.

Sweeny ordered his soldiers to form in the Plaza, and he writes "it

was the general opinion that if my men had not been present that day

the streets of San Diego would have been drenched in blood." Watkins'

leg had to be amputated, and it was presented to Crosthwaite as a trophy

of war. The soldiers remained on guard in Old Town until the Indian

war had ended, and the Hounds had been loaded up and shipped back to

San Francisco.

At Los Angeles, Joshua Bean

led thirty-five men who were to combine forces with a group of Mormons

from San Bernardino and some Californios under Andrés Pico. Meanwhile,

Juan Antonio, upon the urging of a mountain man, and after serious reflection

as to the future of the Indians, decided to again cast his lot with

the Anglos. He laid an ambush for Garra, invited him to a conference,

and took him prisoner. Garra was turned over to the military. Garra's

son and ten followers soon also surrendered themselves to Juan Antonio.

Garra's son and four other

Indians were hastily executed at Chino, San Bernardino County, but the

elder Garra was taken to San Diego, where he was tried before a militia

court martial, headed by Gen. Bean, on charges of treason, murder and

robbery. He acknowledged guilt only in the murders of the American sheepherders,

and testified that the raid on Warner's was made by a small band of

Cahuilla Indians, that he was not with them, and that he had not taken

part in, or ordered, the murders of the four San Diegans at the Hot

Springs. Indian witnesses, accepted in this court, gave conflicting

testimony, but the burden of evidence seemed to show that Garra had

ordered the attacks, but, in a sudden seizure of fear, had feigned illness

and had not taken part in them. Though Indian witnesses had

testified that Marshall and the Indian hanged with him had consulted

with Garra just before the murders, Garra denied they had been involved

in any way. Instead, he insisted that two Californios, Joaquín

Ortega and José Antonio Estudillo, had encouraged the Indian uprisings

in the hope of getting rid of the Americans. These accusations were

denied, and according to memoirs of participants, which included the

leading people of San Diego, were conclusively refuted. Garra

denied plotting an uprising, or leading other attacks on settlers. His

greatest complaint was that he and his people were being taxed by local

and state officials without having any rights extended to them. In other

time, another place, and with paler skin, Garra, a strong traditional

leader amongst his Luiseño people, might have been a symbol of patriotism,

of resistance against unjust taxes, and oppressive government. This first excerpt is part of a more lengthy statement made by Garra after his capture and imprisonment at Rancho del Chino. The interview was published in several California newspapers and raised a stir because of Garra's implication of Mexican (Californios) leaders in a plot to overthrow the Americans. The full text describes Garra's knowledge of the robbings and killings that had recently taken place in southern California. While the structuring of the statement reflects a rather legalistic and stilted translation, the document is important because of the uniqueness of printed accounts of Indian testimonies and statements. "I am a St. Louis Rey [San Luis Rey] Indian, was baptized in Mission of St. Louis Rey, and from my earliest recollection have been connected with the St. Louis Rey Indians. Have had authority over only a portion of the St. Louis Indians. Never had any connections with the Cahuillas. Was appointed by Gen. Kearney, U.S. Army, commander-in-chief of the St. Louis Indians, in the year 1847. I was advised by Joaquin Ortego [Ortega] and Jose Antonio Estudillo, to take up arms against the Americans. They advised me secretly, that if I could effect a juncture with the other Indian tribes of California, and commence an attack upon all the Americans wherever we could find them that the Californians would join with us and help m driving the Americans from the country. They advised me to this course that I might revenge myself for the payment of taxes, which has been demanded of the Indian tribes. The Indians think the collection of taxes from them to be a very unjust measure. " Garra was found guilty of murder and theft on January 17, 1852, and sentenced to be shot. Before the execution Lt. Sweeny talked with Garra in his cell. He wrote that Garra acknowledged that he had induced the Yumas, Cocopas and Cuchanos to unite against the Americans, and that he had urged that a party of 400 be sent against Sweeny's camp at Fort Yuma, to cut him off, and then they were to join in a general descent on the settlements. Though Sweeny had refused

to sit on the court martial, ruling that it was a state matter, and

would not let his soldiers carry out the execution, he did provide arms

and ammunition for the citizens' militia. On the same day that the verdict

was returned, Garra was marched from his cell at the head of an execution

squad of ten men, to a freshly dug grave in the Catholic cemetery. A

large crowd was on hand. He was asked if he had anything to confess.

He answered: "Gentlemen, I ask your pardon for all my offenses, and

expect yours in return." He was blindfolded, told to kneel, and the

order to fire was given. Honor, Integrity and Courage are qualities constantly

expected in all Warriors. Antonio Garra's actions provide a lesson for

today.Tribal pride and a strong sense of history prevails among the

Cahuillas, Luisenos,Kupa and Yuman people. Several reservations have

developed museums and cultural centers (e.g., the Malki Museum on the

Morongo Indian Reservation, the Agua Caliente Cultural Center on the

Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, and the Cupeno Cultural Center on

the Pala Indian Reservation) and the Barona Tribal Museum. Many tribes

have established cultural and educational programs for young people,

elders, and visitors. Educational achievement is a high priority, and

the Tribes are actively engaged in teaching and publishing works about

their traditional culture and history.

|

The

general uprising did not materialize, however, because of the failure

of the Cahuilla Indians as a whole to follow the lead of the men from

Los Coyotes, and because of a change of heart on the part of the Yumas

who had pledged their cooperation to Garra. The Yumas and Cocopas had

halted their own inter-tribal wars long enough to unite for the intended

attack on San Diego, but soon fell out, the Yumas even turning on each

other in a fight over the division of the abandoned sheep of the four

American herders murdered on the desert. Fortunately for the Anglos,

the Indians lacked the ability to pursue an objective.

The

general uprising did not materialize, however, because of the failure

of the Cahuilla Indians as a whole to follow the lead of the men from

Los Coyotes, and because of a change of heart on the part of the Yumas

who had pledged their cooperation to Garra. The Yumas and Cocopas had

halted their own inter-tribal wars long enough to unite for the intended

attack on San Diego, but soon fell out, the Yumas even turning on each

other in a fight over the division of the abandoned sheep of the four

American herders murdered on the desert. Fortunately for the Anglos,

the Indians lacked the ability to pursue an objective.