By Roy Cook

Auka, Wildcat

singer Jon Meza Cuero fulfilled all expectations September 25, 2010. He

was invited by the US Parks Point Loma Committee to be a Tribal representative

part of the 47th annual Cabrillo Day recognition. Superintendent Tom Workman

is there to greet us. He and Karl Pierce are familiar faces from the Parks

Service. All the singers: Jon, Ben Nance, Henry Medibles, Frank Gastelem

and Roy Cook, are pleased to be part of this Tribal recognition again.

Auka, Wildcat

singer Jon Meza Cuero fulfilled all expectations September 25, 2010. He

was invited by the US Parks Point Loma Committee to be a Tribal representative

part of the 47th annual Cabrillo Day recognition. Superintendent Tom Workman

is there to greet us. He and Karl Pierce are familiar faces from the Parks

Service. All the singers: Jon, Ben Nance, Henry Medibles, Frank Gastelem

and Roy Cook, are pleased to be part of this Tribal recognition again.

Jon

respectfully greets Tribal elder Jane Dumas and exchanges pleasantries

in Tipai. They are both linguistic colleagues and fluent native speakers

in the local dialect. A family member and Anthony Pico, former Chairperson

of the Viejas Band also accompanied Jane Dumas.

Jon

respectfully greets Tribal elder Jane Dumas and exchanges pleasantries

in Tipai. They are both linguistic colleagues and fluent native speakers

in the local dialect. A family member and Anthony Pico, former Chairperson

of the Viejas Band also accompanied Jane Dumas.

She

continues to demonstrate her commitment to this celebration again and

again. She participates in many of the activities that offer avenues to

tribal traditional ways. She is a very traditional tribal person. She

is truly an outstanding representative of the ongoing drama of tribal

Americans in a complex urban context. She has endured for many decades.

We are blessed each time we can be together.

She

continues to demonstrate her commitment to this celebration again and

again. She participates in many of the activities that offer avenues to

tribal traditional ways. She is a very traditional tribal person. She

is truly an outstanding representative of the ongoing drama of tribal

Americans in a complex urban context. She has endured for many decades.

We are blessed each time we can be together.

The wind blows free, the sun warms our backs, the rocks remain and the

songs sound again. We can look out across the bay and see the location

of the historical event carried by the songs selected by Jon Meza Cuero.

We are convinced there are ancient ears listening to the songs. Our goal

is to comfort and entertain all past, current and future peoples who hear

these timeless Niemii songs. Jon's selection of songs is particularly

appropriate to the occasion and, as explained to those gathered, are timeless

in the location and meaning of the songs presented.

But, once again, at this year festival, there are a couple of questionable,

curious references that got my 'goat'.

One, the dating of this festival as the 47th annual. I had read a Journal

of San Diego account of the first Cabrillo festival in downtown San Diego

in 1892. From that date to today is 118 years.

Two, at first contact, the term, fearful or great fear is quoted, as a

description of the appearance of members of the Kumeyaay people. The truth

is the local Indian people already knew of the Spanish. They were frightened

of the Spanish because of a series of violent encounters with an inland

Spanish army, looking for the cities of gold, led by Coronado. The local

Tribal people knew from, the eons earlier established American Indian

message runners communication system. Additionally, the sailors were suffering

from scurvy. It is a nasty, physically debilitating maritime disease.

The sailors' 'walking dead' pasty appearance would cause anyone to recoil

with apprehension.

The European summary of Cabrillo's journey in 1542 described the first

encounter of Spaniards and native peoples in this uncharted land. As the

story goes the Europeans approached the beach in a skiff where native

canoes could be seen and MANY Indians gathered. The Kumeyaay "gave

signs of great fear" as they physically described the sightings of

other Europeans by the interior Yuman peoples to Cabrillo and his party,

which was most likely a detachment from the expedition of Francisco Vasquez

de Coronado's exploration party into the New Mexico and Arizona interior.

The Indians indicated that these bearded men carried lances, rode great

horses, and brutally slaughtered many Indians. To assuage their fears,

Cabrillo and his men kidnapped two Indian boys and bribed the leaders

with more gifts. This documented above account verifies this writer's

position of prior American Indian knowledge of the Europeans and the message

system.

With mutual suspicion and violence, the opening page of history in California

began with cautionary actions by both Native Californians and the Spanish.

The Kumeyaay attacked first, perhaps, to protect them and repel the unwanted

visitors, hopefully escaping the fate of the Colorado River Yumans killed

by the soldiers of Coronado. The Spanish, led by Cabrillo, initially chose

restraint (probably because of the weak condition of its scurvy-ridden

crew) so that they might persuade the Indians of Alta California to accept

the imperatives of Spanish culture and religion. From this documented

account, we can conclude there is NO clear legal or just claim for European

imperial colonization. Resistance would continue into the next century

and beyond. Aboriginal land title would continue to rest with the Native

Tribal people.

The first Cabrillo festival 1892 (San Diego Journal Summer 1984, excerpt)

Earliest mention of a civic event to promote the historical significance

of San Diego as the birthplace of California was made by Walter G. Smith.

He was the editor of The Sun and he urged city fathers to promote the

area by holding a celebration. The event would commemorate navigator Juan

Rodriguez Cabrillo's discovery of San Diego Bay three hundred fifty years

before on September 28, 1542. The celebration would afford citizens the

opportunity of acquainting visitors with the city's attributes.1

Although Smith's idea lay dormant until July 16, 1892, when San Diego

Mayor Mathew Sherman called together a large number of prominent interested

citizens, the group moved quickly to expedite plans for the celebration.

Smith pointed out that this seemed to be an appropriate time to celebrate

Spain's discovery and that it would be wise for San Diego to take the

lead as the birthplace of Alta California. Mayor Sherman then appointed

a general committee to formulate ideas for the festivities and in turn

to select subcommittees to work toward the promotion of activities through

the development of a guest list of very important people.2

Elisha S. Babcock, manager of the Hotel del Coronado, offered to contribute

one-tenth of the cost of bringing an Indian tribe to entertain visitors.3

Fundraisers set their goal at $5,000 and began their appeal for financing

the celebration. They hoped to secure $1,000 from the city and county.4

with the expectation that the celebration would "attract the attention

of the entire country to the remarkable inducements for investments .

. .",5 the common council allocated $500. They also felt the press

would prove highly beneficial with heavy coverage providing wide exposure

for the events.6 By calling attention to the area, the press had the ability

to attract many visitors and potential residents to city and county business,

agricultural, and commercial attributes.7

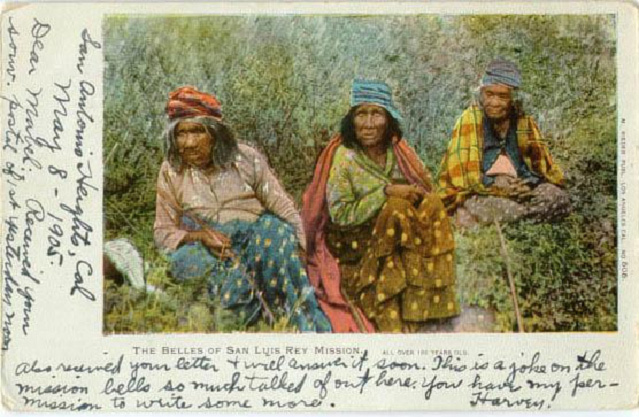

Rapid response to invitations made planning easier. Both the Diegueno

and Luiseno Indian tribes told Father Antonio Ubach they would be anxious

to participate for their food and expenses. According to The Sun, the

"bucks and squaws" planned to wear costumes of olden times while

singing, dancing and playing their ancient, native games. The Indians

for the construction of their huts.8 would use tule from Mission Valley

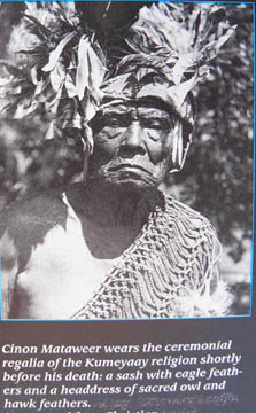

A letter

from Mesa Grande to Father Ubach from two Diegueno chiefs of the Antonio

La Chapa and Cinon Duro. The tribes reported that the young Indians, in

their many hours of daily practice to defeat the Luisenos in dances and

games, had developed sore feet.1

A letter

from Mesa Grande to Father Ubach from two Diegueno chiefs of the Antonio

La Chapa and Cinon Duro. The tribes reported that the young Indians, in

their many hours of daily practice to defeat the Luisenos in dances and

games, had developed sore feet.1

Beginning with the Indians on opening day, the program could now accommodate

vaquero or cowboy games and exhibitions on the closing day.19

The excitement began to mount as the people observed a pavilion, covering

a ground space of 200 x 125 feet, with a framework of poles and ropes

centered by an eighty-foot pole supporting a fifty-foot evergreen canopy

being erected in the Plaza. Enclosed by a high board fence, it was more

difficult to view the Indians constructing their tule huts around the

inner portion of their 200 x 300 foot allocated area on A and Fourth Streets.

A 125-foot central circle provided space for their dances and games.20

The Luiseno Indians from Oceanside preferred to walk rather than ride

in cars to San Diego.21

Flying the Spanish flag, the landing party stepped smartly from the ship's

boat to a gangplank. They proceeded on to the land where they planted

the flag and, in the name of King Charles V of Spain, Cabrillo took possession

of the country.40

As a part of the ceremony, Cabrillo greeted six Indian chiefs: General

Mateo Pia of Patchanga, Pedro Pablo of Panama, Vicente of Temecula, Jose

Manuel of Santa Ysabel and Cinon and Narcison of Mesa Grande. He talked

to them in his native language (Portuguese) while they knelt and kissed

the ground.41

The Indians appeared quite primitive and picturesque in their colorful costumes consisting mostly of body paint and feathers, and abbreviated G-string apron-like garments. Although their native attire may have embarrassed the spectators, the Indians remained stoic and indifferent to any criticism.4

Among the well over fifteen hundred people who joined them parading up

D Street through the town were:

Diegueno and Luiseno Indian tribe representatives, men attired in black

and white calico, most with hats, women in bright calico heavily trimmed

with ribbons; some men stripped to the waist, with their exposed parts

painted bizarre colors while wearing Indian headdresses fashioned from

grain stalks, ferns, leaves and mountain roses; various dignitaries in

open carriages; more Indians in native costumes.

By day, the Indians arranged the costumes for their fiesta activities,

which consisted of games, and dances.52 the preparation involved covering

their bodies and faces with ninety-nine colored clays. After the task

was completed, war paint was prepared and applied by the women. To achieve

the right consistency for the paint mixture, the women chewed one or two

colors, and then spit the combination on the designated area of the man's

body. In the final step, they proceeded to fashion the paint decoration

in stripes and geometrical patterns. The men wore head dresses made of

tule, horsehair, fur, snakeskins, feathers and bird wings. They carried

rattlesnake rattles, crude weapons and bows and arrows. The women dotted

their faces with the paint concoction and wore brilliant ribbons.53 following

the Thursday afternoon speeches in the Plaza; the Indians presented their

fiesta.54

Unfortunately, there had been no arrangements made for witnessing the

event. There was no way to control the squeezing, pushing and cursing,

both loud and muttered, by those in the crowd who anxiously sought a better

vantage point. Consequently, most had a poor view of the sports with the

exception of an occasional glimpse of waving feathers.55

While one man kept time with rattles contained in large pot-like in-struments,

the colorful warriors moved slowly, shoulder to shoulder, around the circle

in the center of the stockade. Their chanting with a range of about three

notes was slow and continuous. From time to time, the musician let out

a loud "ugh!" which prompted an Indian "yell" from

the entire tribe. Then a heavily painted and feathered, agile brave would

whirl around the center of the ring. Generally speaking, the Luiseno men

and women were larger and had finer features than the Dieguenos. Luiseno

men also had the appearance of being fine athletes.56

Who was this Hombre, Cabrillo?

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who died in 1543 while attempting to complete

the first exploration California's coastline,

Though he is generally supposed to have been Portuguese, the evidence

is too scanty to be sure. His birthplace and origins are shrouded in mystery

and controversy, and scholars still debate whether he is from Spain or

Portugal.[1] The name Cabrillo was first mentioned in 1536 and in most

Spanish archives, he is listed as Joao Rodriques Cabrilho (a name spelled

with an "H"). In his younger life, he is simply referred to

as Juan Rodriquez, which is just about as common as John Smith nowadays.

Typically, in the 16th century, a surname was later given to emigrants

in the New World, and it was usually derived from the town, region or

province from which they came.

According to Kelsey, Portuguese historian Cestino Soares insists that

the explorer is from Portugal, but acknowledges that the name Cabrillo

is not known in Portugal. There are, however, several towns, rivers and

mountains named Cabril, and they are often described in the Spanish feminine

adjectival form such as Cabrilla, Cabrillas and Cabrillanes. But they

are never called Cabrillo or Cabrilho.

Manuel Macias, who teaches the history of Latin America at Cabrillo, read

Kelsey's book and was convinced that Cabrillo was of Spanish descent.

"What his grandson said should be proof enough," Macias said.

Macias was referring to sworn testimony given by Cabrillo's grandson,

Geronimo Cabrillo de Aldana, Dec. 4, 1617. Aldana proclaimed then, "My

paternal grandfather, Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo came (to the New World)

from the Kingdoms of Spain in the company of Panfilo de Narvaez."

What did he do to serve his country and his lord?

Cabrillo first arrived in the New World in Jamaica and then traveled with

Narvaez to Cuba in 1511 joining a force of several hundred Spanish soldiers

who were led by Diego Velazquez, later made the first Spanish governor

of Cuba. The Spanish were claiming the island for the kingdom of Spain.

Narvaez led a cuadrilla of 30 crossbowmen, each served by a Jamaican slave.

Kelsey believes Cabrillo went on the mission with Narvaez, who pursued

a bloody, grisly march into the interior of Cuba.

According to Kelsey, the chaplain who accompanied the Narvaez expedition,

Bartolome de las Casas, was horrified by Narvaez's slaughter of the Indians.

Las Casas charged Narvaez himself with killing 2,000 Indians and said

countless others were killed by the horsemen and foot soldiers bearing

swords and crossbows. Kelsey wrote:

"One evening after a long and thirsty march in the interior, Narvaez

and his army arrived at the village of Caonao, where the Indians greeted

them with food and calabashes of water. Thus refreshed, the Spaniards

were invited to enjoy a fish dinner prepared by the villagers. While the

soldiers ate, the natives looked on, examining the horses -- those peculiar

animals the Indians had only heard about but not seen -- and marveling

at the dress and equipment of the Spaniards. As the curious villagers

pressed closer, a soldier suddenly drew his sword and began hacking away

at the bystanders. This was a signal for all to join in the slaughter,

killing young and old, men and women, even domestic animals."

Las Casas, horrified by the scene, abandoned the expedition and said,

"You and your men can go to the devil."

Las Casas later documented the brutal encomienda system which granted

Spanish masters and other proprietors vast tracts of land in which the

residing natives were forced to pay annual tasaciones. These new rulers

were called encomenderos who collected taxes or "tributes" from

the indigenous people in the form of goods or services rendered. Encomenderos

were supposed to indoctrinate the indigenous people with Christianity

and provide protection from external enemies. If the native people refused

to pay the tasaciones or acknowledge Spanish authority, Las Casas said

they were branded as slaves and marched off to the many goldmines in 16th

Century Cuba.

In 1520 Cabrillo, serving as a crossbowman, arrived in Mexico with Narvaez.

The Spanish force was sent with the intent of replacing the renegade Hernan

Cortes, who left Cuba with 300 men to conquer Mexico without the crown's

permission. Using some trickery, Cortes outmaneuvered Narvaez's larger

force and absorbed Narvaez's troops with the promise of Aztec treasure.

Cabrillo was soon made a captain of a cuadrilla, and later served a vital

role in bringing about the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital at

the site of present day Mexico City.

On June 27, 1542 Cabrillo headed north with three vessels: San Salvador,

which he captained and two others.

About August 20, they passed the most northerly point (Punta del Engaño)

reached by Ulloa. On September 28, three months after leaving Mexico,

the ships crossed the future international border and put into a "very

good enclosed port, to which they gave the name San Miguel." It was

our San Diego.

The Indians there were afraid. The Indians told Cabrillo of a large force

of Spaniards just a five-day walk away. They were frightened of the Spanish

because of a previous violent encounter with an inland Spanish army led

by Coronado. This army had wandered for two years, terrorizing the Southwest

and reaching far into the interior of the continent to present-day Kansas.

Cabrillo attempted to send a letter to Coronado via these Indians. That

evening they wounded, with arrows, three men of a fishing party. Instead

of marching forth in retaliation, Cabrillo sailed slowly on into the harbor,

caught two boys, gave them presents and let them go.

On Sept. 17, 1542, Cabrillo claimed California for the Spanish Crown.

"Every place he (Cabrillo) discovered, he was to take possession

for the king of Spain," said Macias. "All explorers were told

that when they encountered a new group of Indians, they were required

to read them this explanation, called a requerimiento. It was an act of

taking possession of the land."

Macias said the requerimiento was read in Spanish and Latin, neither of

which languages the Indians understood. A ritual ceremony was also performed:

four pebbles were tossed in four directions and water was spilled on the

land as a physical act of taking possession. Macias said the requerimiento

instructed the Indians to submit to Spanish authority under religious

justification as ordered by the pope.

The beginning of the letter, translated into English read: "On the

part of the King, Don Fernando, and of Dona Juana, Queen of Castile and

Leon, subduers of the barbarous nations, we their servants notify and

make known to you, as best we can, that the Lord our God, Living and Eternal,

created the Heaven and the Earth, and one man and woman, of whom you and

I, and all the men of the world, were and are descendants, and all those

who came after us. But, on account of the multitude which has sprung from

this man and woman in the five thousand years since the world was created,

it was necessary that some men should go one way and some another, and

that they should be divided into many kingdoms..."

There is no firm agreement about the cause or place of his death, up the

coast and most likely of gangrene read most conclusions.

________________________________________________________

Source: San Diego Journal, 1984: San Diego's First Cabrillo Celebration,

1892: Sally Bullard Thornton, 1984.

Biography of Cabrillo: Harry Kelsey, 1986.