By Roy Cook

John Muir could not see the Indians for the trees. We do not know why Muir was blind regarding the original people in all of the beautiful National Park locations he waxed about so eloquently. Indian people are the true conscience of the American character. John Muir saw the trees and sat on the glaciers but did not note the Tribal people that were living in Yosemite at the same time. This omission is not unique to this individual. We can see time after time, area after area; Tribal people are invisible to non-Indian eyes. We must always look to the future and our Indian children.

The KPBS Ken Burns series on the National parks is a beautifully presented cosmetic overview of events that resulted in the largest land grabs of Federal/Indian land. The series is entertaining and informative but the basic truth of the settled existence of the original Americans that lived in these lands for 50,000 or more years is sadly lacking.

Yosemite

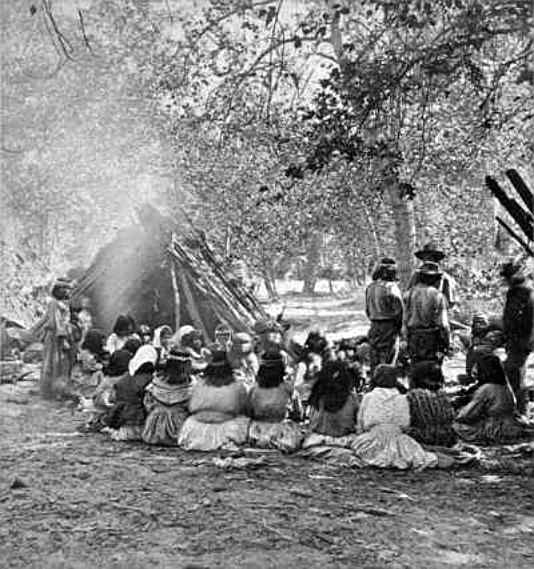

around 1870, by Eaweard Muybridge, the famous photographer.

The illegal invasion of California and the illegal US Senate disregard of the Federal Treaties of Peace and Friendship is one of the saddest chapters in Western American history. Included below are some of the original articles of non-military brigands who tried to claim military justification for their self-serving land and resources greed. They are in the original writer’s text for you to determine your own judgment of events. Our US Constitution LEGALLY will not allow the taking of land without due process and just compensation. Might does not make right. No phony war against peaceful people. No ratified Treaty, no legal claim to California. It is all Indian land.

The Miwok called

Yosemite Ahwahnee or “mouth,” because the valley walls resembled

a gaping bear’s mouth.

L. H. Bunnell of the Mariposa Battalion named Yosemite Valley in 1851. The Battalion was formed by local miners in the foothills after neighboring tribes, feeling encroached on their lands, raided Savage’s Trading Post, killing several people there at the time. Mr. Bunnell named the valley in honor of the tribe they were about to capture and drive out of their home, Yosemite Valley. Pioneers at the time often disregarded native place names or didn’t know them and used place names of their own making.

The Yosemite people called Yosemite Valley Awooni or Owwoni for (gaping) “large mouth,” where the stem Awo or Owwo means “mouth” and the suffix ni means “large.” This referred to the appearance of the Yosemite Valley walls from the village of Ahwahnee, which was located on the valley floor. The spelling used by Bunnell was “Ahwahne” and later “Ahwahnee.” The Yosemite people called themselves as Ah-wah-ne-chee, or “dwellers of Ahwahnee.” Ahwahnee originally referred to the largest and most powerful Indian village in the valley (located 1/2 mile west of Yosemite Village and south of Northside Drive), but the word also came to mean the entire valley.

When asked, Chief Tenaya, tried to explain the meaning of “Ahwahnee” by using sign language. Tenaya “by the motion of his hands, indicated depth, while trying to illustrate the name, at the same time plucking grass which he held up before me.” Major Savage mistakenly interpreted Ahwahnee to mean “deep grassy valley,” when Tenaya was signing “mouth.”

Miwok or Me-wuk

(Southern dialect), by the way, is the Miwok word for “people.”

John Muir's attitude

toward American Indians evolved over the course of his life. From the

KPBS documentary, we learn of his strong upbringing as a Christian and

his ability to recite the New Testament. From later reports, we learn

that his earliest encounters with American Indians were with the weary

tribes of Winnebago Indians in Wisconsin, who begged for food and stole

his favorite horse. In spite of that, he had a great deal of sympathy

for them for "being robbed of their lands and pushed ruthlessly back

into narrower and narrower limits by alien races who were cutting off

their means of livelihood." His early encounters with the Digger

Indians in California left him feeling ambivalent after seeing their lifestyle,

which he described as "lazy" and "superstitious".

Keeping in mind the climate of opinion that was prevalent at the time

we can still expect better empathy and not just sympathy from Muir. Carolyn

Merchant criticized Muir, believing that he wrote disparagingly of the

American Indians he encountered in his Sierra Nevada travels in 1868 (My

First Summer in the Sierra (1911)). In the book, Muir focus is still on

the trees when he actually praised the American Indians for their low

impact on the wilderness, and disparaged the white man's comparably heavy

impact. Muir's attitudes towards American Indians grew more respectful

over time, especially after he lived with them while traveling in the

California and Pacific Northwest wilderness.

California and the Indian Wars: Mariposa Indian War, 1850-1851

By Warren A. Beck and Ynez D. Hass

The Mariposa Indian War was the most famed Indian encounter with miners in the southern Sierra region and led to the discovery of Yosemite Valley. In 1849, as gold seekers invaded the country immediately west of the present Yosemite National Park they found one of the more densely populated Indian areas of the state. This was a region where acorns were abundant and game was plentiful below the winter snow line. Unfortunately, gold was also easily found along the numerous mountain strearns. At first, the Indians (mainly Mono Piutes) welcomed the white man and the goods, which could be obtained by trade, but resentment grew as virtually every valley was taken over by the newcomers.

To a certain extent, the story of this clash between Indian and white is the saga of James D. Savage, one of the most remarkable of the many characters of the Gold Rush era. A tall blue-eyed blonde who always wore red shirts to better impress the Indians, Savage had been a Bear Flagger, a one-time Sutter employee, and the one who was reported to have excited San Franciscans by hauling a barrel of gold dust through a hotel lobby. Establishing trading posts on the Fresno River and Mariposa Creek, he reportedly traded to the Indians "an ounce of gold [for] ... five pounds of flour, or a pound of bacon, a shirt required five ounces, and a pair of boots or a hat brought a full pound of the precious metal." Something of a linguist, Savage quickly learned most of the Indian tongues. He further ingratiated himself by taking wives from several different tribes (one authority said thirty-three!). It is hard to determine if the initial Indian attack was directed against Savage or against whites in general.

Through his wives Savage learned of a planned Indian uprising in September 1850, but other whites did not take the warning seriously. In December, Savage's Trading Post was destroyed at Fresno Crossing, and three of his men killed. A force under Sheriff James Burney clashed indecisively with the Indians on January 11, 1851. An appeal to the Governor for help led to the organization of the Mariposa Battalion under "Major" James D. Savage, with three companies led by Captain John J. Kuykendall, Captain John Boling, and Captain William Dill. Kuykendall's company went southward to the King and upper Kaweah while the other two companies, in three campaigns, followed the Indians into the mountains.

The Mariposa Battalion

was forced to wait before attacking the Indians while. a federal Indian

commission, composed of Redick McKee, George W. Barbour, and Oliver M.

Wozencraft, sought a peaceful solution. On March 19, 1851, the Commissioners

signed a treaty at Camp Fremont with six tribes. However, the Yosemites

(Miwok) and Chowchillas (Yokut) were absent, so the campaign against them

began on March 19. The companies of Boling and Dill moved against the

Yosemites, and discovered their valley on March 27. However, the battalion

was forced to march in 3- to 5-foot snowdrifts and in rain and sleet and

found few Indians. The second campaign began on April 13, against the

Chowchillas, and destroyed Indian food stores, but again the natives were

able to elude their pursuers. However, the death of their chief induced

the Chowchillas to surrender and accept reservation status. When the Yosemites

refused to come to Camp Barbour and make peace, the third campaign launched

against them, but with no more success than the others. However, as in

all Indian wars, the result was foreordained; the Yosemites were captured

at Lake Tenaija (or Tenaya, named for their chief) on May 22, and forced

to accept reservation life.

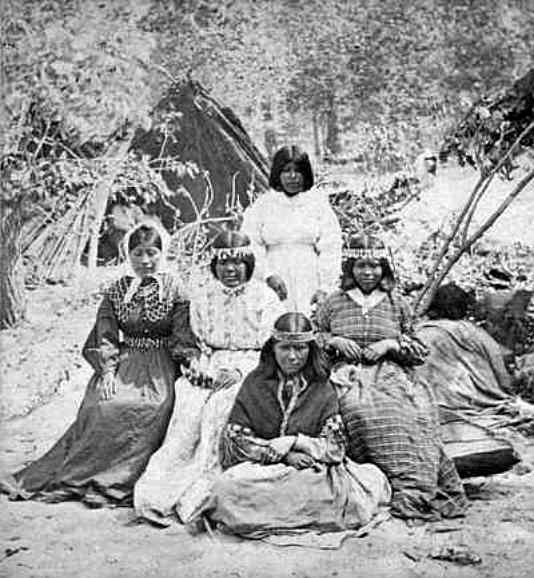

Muybridge photographs Albert Bierstadt painting a an Indian man.

Indian people are the true conscience of the American character.

Discovery of Yosemite: Lafayette H. Bunnell (chapter 3 excerpt.)

Major Savage gave some orders to Captain Boling, which was not then understood by me. On again resuming our march, the Major, with “Bob,” started at a rapid step, while the others maintained a slow gait.

I followed the Major as I had been accustomed during the march. I soon heard an audible smile, evidently at my expense. I comprehended that I had somehow “sold” myself, but as the Major said nothing, I continued my march. I observed a pleased expression in the Major’s countenance, and a twinkle of his eyes when he glanced back at me as if he enjoyed the fun of the “boys” behind us, while he increased his speed to an Indian jog-trot. I determined to appear as unconscious, as innocent of my blunder, and accommodate my gait to his movements. My pride or vanity was touched, and I kept at his heels as he left the trot for a more rapid motion. After a run of a mile or more, we reached the top of a narrow ridge which overlooked the village. The Major here cast a side glace at me as he threw himself on the ground, saying: “I always prided myself on my endurance, but somehow this morning my bottom fails me.” As quietly as I could I remarked that he had probably been traveling faster than he was aware of, as “Bob” must be some way behind us. After a short scrutiny of my unconcerned innocence, he burst into a low laugh and said: “Bunnell, you play it well, and you have beaten me at a game of my own choosing. I have tested your endurance, however; such qualifications are really valuable in our present business.” He then told me as I seated myself near him, that he saw I had not understood the order, and had increased his speed, thinking I would drop back and wait for the others to come up, as he did not wish to order me back, although he had preferred to make this scout alone with “Bob,” as they were both acquainted with the band and the region they occupy. While we resting “Bob” came up. The Major gave him some direction in an Indian dialect I did not understand, and he moved on to an adjoining thicket, while the Major and myself crawled to the shelter of a bunch of blue brush (California lilac), just above where we had halted.

After obtaining the desired information without being seen, Bob was sent back to Captain Boling to “hurry him up.” While awaiting the arrival of our command, I, in answer to his inquiries, informed the Major that I had come to Detroit, Michigan, in 1833, when it was but little more than a frontier village; that the Indians annually assembled there and at Malden, Canada, to receive their annuities. At that time, being but nine years of age, and related to Indian traders, I was brought in contact with their customers, and soon learned their language, habits and character, which all subsequent attempts to civilize me had failed entirely to eradicate. This statement evidently pleased the Major, and finding me familiar with frontier life, he continued his conversation, and I soon learned that I was acquainted with some of his friends in the Northwest. I have related this incident because it was the beginning of an intimate friendship which ever afterward existed between us.

On the arrival of Captains Boling and Dill with their respective companies, we were deployed into skirmish line, and advanced toward the encampment without any effort at concealment. On discovering us the Indians hurriedly ran to and fro, as if uncertain what course to pursue. Seeing an unknown force approaching, they threw up their hands in token of submission, crying out at the same time in Spanish, “Pace! pace!” (peace! peace!) We were at once ordered to halt while Major Savage went forward to arrange for the surrender. The Major was at once recognized and cordially received by such of the band as he desired to confer with officially. We found the village to be that of Pon-wat-chee, a chief of the Noot-chü tribe, whose people had formerly worked for Savage under direction of Cow-chit-ty, his brother, and from whose tribe Savage had taken Ee-e-ke-no, one of his former wives. The chief professed still to entertain feelings of friendship for Savage, saying that he was now willing to obey his counsels. Savage, in response, lost no time in preliminary affairs.

He at once told the chief the object of the expedition, and his requirements. His terms were promptly agreed to, and before we had time to examine the captives or their wigwams, they had commenced packing their supplies and removing their property from their bark huts. This done, the torch was applied by the Indians themselves, in token of their sincerity in removing to the Reservations on the Fresno.

By the Major’s orders they had at once commenced their preparations for removal to a rendezvous, which he had selected nearly opposite this encampment, which was accessible to horses. This plateau was also the location designated for our camp. This camp was afterwards used by an employé at the agency, whose name was Bishop, and was known as Bishop’s Camp. It is situated on an elevated table, on the right side of the valley of the South Fork.

While the Indians were preparing for their transfer to the place selected, our tired and hungry men began to feel the need of rest and refreshments. We had traveled a much longer distance since the morning before than had been estimated in expectation of a halt, and many of the men had not tasted food since the day before.

John Hankin told Major Savage that if a roast dog could be procured, he would esteem it an especial favor. Bob McKee thought this a capital time to learn to eat acorn bread, but after trying some set before him by “a young and accomplished squaw,” as the Major cynically termed her, concluded he was not yet hungry enough for its enjoyment.

A call was made for volunteers to go back to bring up the reserve and supplies, but the service was not very promptly accepted. McKee, myself and two others, however, offered to go with the order to move down to the selected rendezvous. Three Indians volunteerd to go with us as guides; one will seldom serve alone. We found the trail on the right bank less laborious to travel than was expected, for the snow had mostly disappeared from the loose, sandy soil, which upon this side of the river has a southwesterly exposure. On our arrival in camp preparations were begun to obey the order of the Major. While coffee was being prepared Doctor Bronson wisely prescribed and most skillfully administered to us a refreshing draught of “Aqua Ardente.” This is the lubricant of the west, Whisky.

After a hasty breakfast, we took to our saddles, and taking a supply of biscuits and cold meat, left the train and arrived at the new camp ground just as our hungry comrades came up from the Indian village. The scanty supplies, carried on our saddles, were thankfully received and speedily disposed of. The Indians had not yet crossed the river. We found that we had traveled about twelve miles, while our comrades and the captives had accomplished only three.

From this camp, established as our headquarters, or as a base of operations while in this vicinity, Major Savage sent Indian runners to the bands who were supposed to be hiding in the mountains. These messengers were instructed to assure all the Indians that if they would go and make treaties with the commissioners. they would there be furnished with food and clothing, and receive protection, but if they did not come in, he should make war upon them until he destroyed them all.

Pon-wat-chee had told the Major when his own village was captured, that a small band of Po-ho-no-chees were encamped on the sunny slope of the divide of the Merced, and he having at once dispatched a runner to them, they began to come into camp. This circumstance afforded encouragement to the Major, but Pon-wat-chee was not entirely sanguine of success with the Yosemites, though he told the Major that if the snow continued deep they could not escape.

At first but few Indians came in, and these were very cautious—dodging behind rocks and trees, as if fearful we would not recognize their friendly signals.

Being fully assured by those who had already come in, of friendly treatment, all soon came in who were in our immediate vicinity. None of the Yosemites had responded to the general message sent. Upon a special envoy being sent to the chief, he appeared the next day in person. He came alone, and stood in dignifed silence before one of the guard, until motioned to enter camp. He was immediately recognized by Pon-wat-chee as Ten-ie-ya, the old chief of the Yosemites, and was kindly cared for—being well supplied with food—after which, with the aid of the other Indians, the Major informed him of the wishes of the commissioners. The old sachem was very suspicious of Savage, and feared he was taking this method of getting the Yosemites into his power for the purpose of revenging his personal wrongs. Savage told him that if he would go to the commissioners and make a treaty of peace with them, as the other Indians were going to do, there would be no more war. Ten-ie-ya cautiously inquired as to the object of taking all the Indians to the plains of the San Joaquin valley, and said: “My people do not want anything from the ‘Great Father’ you tell me about. The Great Spirit is our father, and he has always supplied us with all we need. We do not want anything from white men. Our women are able to do our work. Go, then; let us remain in the mountains where we were born; where the ashes of our fathers have been given to the winds. I have said enough!”

This was abruptly answered by Savage, in Indian dialect and gestures: “If you and your people have all you desire, why do you steal our horses and mules? Why do you rob the miners’ camps? Why do you murder the white men, and plunder and burn their houses?”

Ten-ie-ya sat silent for some time; it was evident he understood what Savage had said, for he replied: “My young men have sometimes taken horses and mules from the whites. It was wrong for them to do so. It is not wrong to take the property of enemies, who have wronged my people. My young men believed the white gold-diggers were our enemies; we now know they are not, and we will be glad to live in peace with them. We will stay here and be friends. My people do not want to go to the plains. The tribes who go there are some of them very bad. They will make war on my people. We cannot live on the plains with them. Here we can defend ourselves against them.”

In reply to this Savage very deliberately and firmly said: “Your people must go to the Commissioners and make terms with them. If they do not, your young men will again steal our horses, your people will again kill and plunder the whites. It was your people who robbed my stores, burned my houses, and murdered my men. If they do not make a treaty, your whole tribe will be destroyed, not one of them will be left alive.” At this vigorous ending of the Major’s speech, the old chief replied: “It is useless to talk to you about who destroyed your property and killed your people. If the Chow-chillas do not boast of it, they are cowards, for they led us on. I am old and you can kill me if you will, but what use to lie to you who know more than all the Indians, and can beat them in their big hunts of deer and bear. Therefore I will not lie to you, but promise that if allowed to return to my people I will bring them in.” He was allowed to go. The next day he came back, and said his people would soon come to our camp; that when he had told them they could come with safety they were willing to go and make a treaty with the men sent by the “Great Father,” who was so good and rich. Another day passed, but no Indians made their appearance from the “deep valley,” spoken of so frequently by those at our camp. The old chief said the snow was so deep that they could not travel fast, that his village was so far down (gesticulating, by way of illustration, with his hands) that when the snow was deep on the mountains they would be a long time climbing out of it.

Indian people are the true conscience of the American character.

SURVIVORS OF EARLY WARS Widows of Those "Who Fought the Red Men Will

Participate -- Cost to the Government.

*

Special to The

New York Times.

January

28, 1900, Wednesday

Page 3, 569

words

This is evidence that the veterans and widows of the Indian Wars were

being looked after by the Federal government. It would be 100 years for

the US Government to offer a pitiful scrap of a token payment for the

prime land and billions of dollars in gold and timber extracted. In 1851-2

Federal Indian commission, composed of Redick McKee, George W. Barbour,

negotiated 18 Treaties and Oliver M. Wozencraft, sought a peaceful solution.

On March 19, 1851, the Commissioners signed a treaty at Camp Fremont with

six tribes. These Treaties were not ratified therefore; the US Government

illegally took and or condoned the theft of Indian land. In 1954, a per

capita payment was made of $157 to the descendents. In 1968, a payment

for the rest of California was made: $628 dollars. That is not justice.

It is a travesty. Why is John Muir so quiet on this injustice?

Resources:

Fleck, Richard F.,

"John Muir's Evolving Attitudes toward Native American Cultures"

American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Feb., 1978), pp. 19-31

http://www.indiancanyon.org/t18TreatyList.html

http://thehive.modbee.com/?q=node/1620